New Evidence for the Early History of the Sheaffer Pen Company:The First Sheaffer Pens (First in a Series)[original version, The Pennant, Spring 2001]

The early history of Sheaffer production has long been obscure. Walter A. Sheaffer's first fountain pen patent was issued in 1908, but the earliest evidence for large-scale production dates to around 1913 or 1914. Indeed, the earliest Sheaffer barrel imprint seen with any consistency is the one with the central "SELF-FILLING" logo in an oval and patent dates of 1908 and December 12, 1912 (fig. 1). This imprint predates the one adopted following the issuance of patent 1,114,052 on October 20, 1914, and must therefore be dated somewhere between mid-December 1912 and late October 1914 [it is now believed that this imprint remained in use until c. 1916/17 -- D.].

Fig. 1: Detail of barrel imprint of c. 1913-18 [see text above] Nonetheless, something must have come before. The pens with the imprint of c. 1913 were clearly produced in large numbers, judging from the number of surviving examples, and they show none of the wide variations to be expected in the first production run of a brand-new company. Yet only a handful of likely precursors have turned up to date, so few that dating them and fitting them into any sort of pre-1913 chronology has until now been largely guesswork. The records of the patent dispute, however, do much to clarify the early history of Sheaffer's penmaking. And while the testimony of the various parties may be in conflict concerning who invented what, there is near-complete accord in the testimony concerning the history of production. As it turns out, Sheaffer pen production did not begin until 1912. At the end of 1911, R.G. Dun & Co. had rated Walter A. Sheaffer's creditworthiness, evaluating all his other enterprises (his jewelry business being the most significant) but made no mention whatever of any activity involving pens (655.345). In January of 1912, however, Sheaffer went to New York City to have pens made to his patent designs. The first samples received were made up into pens at the end of February or the beginning of March (520.210). The first significant orders appear not to have come in until June (521.211), and the first deliveries did not take place until the end of July or early August (524.214, 637.327).

Fig. 2: Detail from 1908 patent, showing single-bar mechanism

Fig.

3: Detail from 1912 patent, showing production version of single-bar mechanism

While these early production pens were all lever-fillers (sub-brands excepted), their internal mechanism was radically different from the later Sheaffers with which we are all familiar. The original Sheaffer lever-filler (the "single-bar" pen) used a rigid pressure bar that could slide up and down on a metal attachment anchored in the end of the barrel. This springless mechanism was similar to the arrangement used in the 1920s and 1930s by Wahl, but without any linkage between the lever and the pressure bar and without any provision to hold the lever closed, apart from the resilience of the ink sac (figs. 2, 3). Not surprisingly, the pressure bar was prone to getting out of place, and as soon as the sac began to take a set, the lever would flop loose.

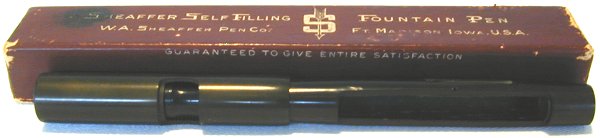

Fig. 4: Detail from 1914 patent, showing double-bar mechanism The so-called "double-bar" pen was a vast improvement, and its combination of a rigid pressure bar with a slotted spring through which the lever operated (fig. 4) was essential to Sheaffer's long-term success. The first double-bar pens were shipped at the beginning of April 1913 (653.343); by February 1915 some 200,000 had been produced (78.802), eclipsing the total production of around 35,000 single-bar pens (639.329, 864.554). It seems that after an initial move to clear out all of the remaining single-bar pens in stock, Sheaffer switched course and made a concerted effort to get back as many old pens as possible, giving out new double-bar pens in exchange. The old holders were initially scrapped, until it was realized that they could be recycled as cutaway demonstrators ("skeleton" pens is the term used in the transcripts) for the new double-bar mechanism (825.515, 1635.555). This recycling was still under way in June 1915, at which time a demonstrator was being sent out with every shipment (710.400). Although there was no formal recall of the single-bar pens, the exchange effort appears to have been very successful: hardly any appear to have survived to the present day. From the outside, single-bar Sheaffers can be identified by their levers, which were significantly wider and somewhat longer than their later counterparts, and were set close to the end of the barrel, so close, that in some cases they could not be operated when the cap was posted (774.464, 848.538). Internally, it seems that all production single-bar pens used the inserted end piece upon which the pressure bar slid (752.442). The patent for this end piece was applied for on March 21, 1912, and was awarded on December 10 of the same year. The idea for this design preceded the patent application by at least a few months, however, as Sheaffer was already commissioning dies during his January trip to New York (590.280, 596.286). The court records give no indication of the imprints used on the single-bar pens, though it is clear that they were imprinted. It is probable that the pens made from around mid-December 1912 to the end of March 1913 bore the same SELF-FILLING in an oval imprint used for the early double-bar pens (fig. 1), for that same logo also features in Sheaffer's first catalog, prepared at the end of 1912. Pens produced prior to mid-December 1912 undoubtedly carried an imprint referring to Sheaffer's patent of 1908. The pen profiled as "The Earliest Sheaffer Pen" a few years back in the PENnant (IX/3-4 [1996], pp. 10-11) carries just such an imprint, and likely belongs to these first months of manufacture. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the Sheaffer pens produced in 1912 were not all alike, and that the first few months of production constituted a period of experimentation and market research, all by trial and error. During this period variations were numerous. As manufacturing techniques were worked out and customer preferences emerged, a more standardized pen emerged. Sheaffer testified there were "dozens of changes in little details . . . between January and June, 1912" (653.343), and until the first orders came in June, no one had any idea of what proportion of different kinds of pens to have made up and in stock (794.484). This process appears to have run its course relatively quickly, for by the time of publication of Sheaffer's first catalog in February 1913, the models illustrated varied only in size, color, and applied decoration. Sheaffer's own 1915 testimony, however, makes it clear that a few of the first production pens were slip-caps (as shown in the patent diagrams of 1908 and 1912. (figs. 2, 3) Others had clips (520.210, 794.484). There were also some pens with extra-long levers, which were made in April 1912 but not shipped to the trade (649.339, 652.342). Most unexpectedly, the first production pens were equipped with a broad, finned feed, the narrow "keel" feed being adopted only after the first design proved unreliable (559.249, 1135.55). The pen illustrated in the PENnant was made with threads at both ends of the barrel, a feature not specifically mentioned in the court records and not shown in the first catalog. What about Sheaffer pens prior to 1912? The patent dispute testimony indicates that only a very few handmade models were put together before that year (687.377). The majority of these were strictly for experimental purposes, with some made from other pens. The model first shown to Schnell was originally a Mooney blow-filler (1984.904). Many of these models appear to have been quite roughly finished, with some lacking vital parts such as caps, nibs, or feed assemblies. In all likelihood, none of these bore Sheaffer imprints of any sort. The survival rate of the first production pens appears to be extremely low: of some 35,000 made, only a handful are now extant. Not surprisingly, no preproduction models are known today, and though one might have expected Sheaffer's original patent models to have been preserved in the company's archives, even in 1915 Sheaffer had trouble locating the model submitted for the 1914 double-bar patent. (It finally turned up the next year in the offices of his Washington, DC patent attorneys, partially disassembled. [230.914]). According to Sheaffer's testimony, only one or two complete models were made up for his original 1908 patent; these differed from the production pens in using two transverse pins through the barrel to hold the pressure bar instead of an inserted end piece (521.111, 687.377, 892.582). This construction is clearly shown in the 1908 patent drawings (fig. 2). Interestingly enough, there appears to have been an initial, abortive attempt to begin pen manufacture shortly after the 1908 patent was granted. Sheaffer testified that he had placed an order for "holders" (i.e. caps and barrels, and likely feed assemblies) with George T. Byers of New York, but the deal did not work out and Sheaffer never took delivery (587.277). These pens were to have used the two transverse pins to hold the pressure bar, and a locking device to secure the lever was contemplated (590.280). When Sheaffer did give pen manufacture another try a few years later, it was thanks to the encouragement and advice of George Kraker, a controversial figure, later Sheaffer's bitter opponent, but at the time a well-traveled pen distributor with extensive knowledge of the pen business. Later, Sheaffer tried to downplay Kraker's contribution, but letters between the two suggest that Sheaffer relied heavily on Kraker. It was he who wrote to Sheaffer during one of the latter's early trips to New York in search of contract manufacturers, recommending Mabie Todd as top-line and stating that Sheaffer would need look no further if they would agree to make his pens (892.582). As it turned out, Sheaffer had to keep looking. He was back in New York again in January 1912, and ended up at Julius Schnell's factory (588.278). Schnell had been producing hard rubber parts for a Who's Who of penmakers, Conklin being his largest customer at the time. Sheaffer and Schnell managed to come to an agreement although the exact chronology is a bit confused. By the end of the year Schnell had a contract to produce 1000 holders per week for Sheaffer (820.510). Schnell continued supplying Sheaffer until the outbreak of war in 1914, but did relatively little business with Sheaffer between then and 1915 (629.319). Sheaffer claimed this was due to the impact of the war on sales, yet it is a matter of record that Sheaffer also began making its own holders around the same time. Shortly after Schnell declined Sheaffer's offer to take over his factory in exchange for Sheaffer stock (1956.876). Even in 1915, however, Sheaffer was still depending on outside suppliers for at least some of its holders, as Sheaffer testified that Standard Vulcanite of New York became a subcontractor around the time Schnell gave his first deposition (1031.721). As long as Schnell was producing for Sheaffer he produced every hard rubber part: caps, barrels, sections, and feeds. Early on, his factory was even setting nibs for Sheaffer, although that operation was soon transferred to Fort Madison, supposedly on Schnell's recommendation (1955.875). Schnell did not produce metal parts. For the single-bar mechanism, Sheaffer arranged to have stamping dies made up in New York. For the more complex double-bar assembly, Sheaffer contracted to have the bars produced by a firm in Waterbury, Connecticut (2004.924). Nibs came from both Chicago and New York. The court records state unequivocally that the New York nibs were from P.D. Collins, but the source of the Chicago nibs is less clear (1637.557, 1681.601, 1955.875). In his 1937 autobiography, Walter A. Sheaffer wrote that Grieshaber was the supplier, yet Harvey Craig, Sheaffer's former factory manager, testified in 1915 that the nibs were coming from C.E. Barrett. Since Barrett himself testified at another point that his firm only fabricated hard rubber, not metal, it might have been that Barrett was acting as an intermediary and Grieshaber was the actual maker. On the other hand, in 1937 Sheaffer may not have wanted to make mention of Barrett, whom he later sued for patent infringement for making holders for the Kraker Pen Co. Initially, pens were assembled in an area in the back of Walter Sheaffer's jewelry store. Towards the end of January 1913, when the company was first incorporated, operations were moved to rented space in the Hesse (pronounced "Hessie") Building. For the most part, "production" consisted of putting together components purchased from outside suppliers. Nonetheless, some parts needed finishing -- the end pieces, for example, had to be smoothed with great care to prevent the pressure bars from catching. (329.19, 558.248) Others had to be fabricated by hand, at least at first. Ferdinand A. (Fred) Pollmiller, a Sheaffer employee who worked on pens before the move to the Hesse building, testified, "I sawed the levers out of wire, filed them down, drilled the holes, and sawed the slot in the end and polished them. Then I shaped end-pieces, I put the notches in the bars, I set some nibs, I put the pens all together, I did put the rivets in all the gold pens through the levers and polished the gold pens." (330.20, 360.50) The handful of employees all had to juggle multiple tasks, and even the secretaries and bookkeepers put in time assembling, testing, and packing pens. It is hard to grasp quite how fast Sheaffer manufacture took off, from such makeshift handwork to assembly of 1000 pens per week, all in less than a year and without any national advertising. Retail prices for the single-bar lever-fillers ran from $2.50 up, while the cost of manufacture of the basic No. 34 was estimated at 70 cents, or 75 cents if equipped with a clip (710.400, 1901.821). Return on capital in 1913, the first year of incorporation, was around 50%, and the company's growth was still accelerating. Postscript: At the 2001 Chicago Pen Show, Dan Reppert and Cyndie Schlagel showed me two interesting discoveries, reproduced below by their kind permission. The pen is a very early Sheaffer which appears to have been made prior to December 1913 as a single-bar pen, only to be subsequently recycled as a cutaway demonstrator for the double-bar mechanism. The box was found separately; it appears to have housed a single-bar pen, as the logo is the same as that found imprinted on the pen.

The imprint, shown in the detail below, is also the same as that borne by the early pen profiled in the Pennant article referenced above. Other examples of early pens with this imprint have also been reported to us, and it now seems evident that this was indeed Sheaffer's original imprint of 1912.

If you have or are aware of any similarly early specimens, please let us know. We would also be interested in early Sheaffer advertising or sales literature, especially any using the arrow motif or slogans such as "Bull's Eye of Perfection" or "The New Favorite".

Copyright © 2001-2003, revised 2015 David Nishimura. All rights reserved |